What direction will EU take after the European Parliament elections?

Article

Timo Miettinen

University Researcher, Network for European Studies, Helsinki University

Online publication Future of Europe

© SOSTE Finnish Federation for Social Affairs and Health, February 2019

Mistrust toward the Union, needs to reform the economic policy and the increasing importance of intergovernmental cooperation characterise the EU, which is undergoing a transition period. The intergovernmental development is not necessarily desirable for small countries like Finland, and clarifying the EU level power relations is important. The upcoming Parliament elections may have a decisive role in determining whether intergovernmental cooperation outside the EU law will be increased.

The European Union is said to be living a transitional period. In recent years, problems have been caused by the prolonged economic crisis and the related political and social problems, as well as the refugee crisis testing the unity of the Union, and the increasing instability in the near regions. The rule of law is challenged by Eastern Europe, and in many countries the traditional party system is challenged by the Eurosceptic parties.

The 2016 national referendum on Brexit of Great Britain aggravated the problems in a unique way. The Brexit process has undermined the perception of a constantly converging union and even brought up the question of its disintegration in its present form. But the difficulties involved in Britain’s severance agreement have shown how tightly intertwined the member states are in the institutions governed by EU law. Exiting the Union is difficult and expensive.

However, the European Union has begun a series of measures to tackle these problems. The Rome Declaration on the Future of the European Union signed by 27 heads of state or government and the leaders of the European Council, European Parliament and the European Commission in Rome on 25 March 2017 may be perceived as a launch for this process.

The process is commonly called a reflection on the future of the European Union. The White Paper published by the Commission in March 2017 and five discussion papers e.g. on the development of the Monetary Union and security seek to provide an idea of the kind of measures the Union could promote in individual areas of policy. The most important for Finland would seem to be issues related to the development of the eurozone, a common defence policy, migration management and trade policy.

The reflections on the future by the European Council and the European Commission are related not only to individual areas of policy but also the role of the EU as a political institution and more widely, to the democratic legitimacy of the EU. The euro crisis which began in 2009 has challenged many of the present perceptions on the internal division of power of the Union and the competence of the individual institutions. Instead of federalism, we have drifted into a situation where the role of some of the big member states has become dominant. At the same time, the reforms made in the eurozone have created new institutional structures outside the traditional EU law. Many of the suggestions of Juncker’s Commission are tightly related to the changing political nature of the Union.

The euro crisis has challenged the current thinking on the internal distribution of power in the Union and the competence of individual institutions.

In this article, I will focus on three lines of development which characterise the above-mentioned logic of crisis and reform. These include the trust felt toward the EU, the reform of economic policy and the new intergovernmental nature of the EU. These lines of development offer a framework against which individual measures of policy may hopefully be assessed later.

EU and democratic legitimacy

The main question in assessing the democratic legitimacy of the EU politics is the trust felt by the citizens toward the Union. It is a commonly held view that the euro crisis and the refugee crisis have increased mistrust toward the Union throughout Europe. Mistrust is often perceived as an impediment to institutional reforms.

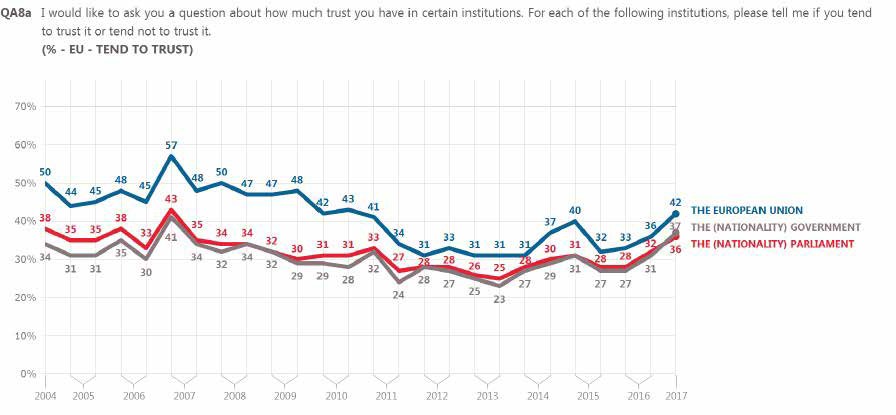

The view is one-sided, however, The Eurobarometer (see picture below) measuring various attitudes towards the Union shows that the trust felt toward the Union is consistently higher than the support received by the national institutions from their citizens. The trust toward the Union and the national institutions is inversely related to economic development: from 2009 onwards, weak economic development has undermined the credibility of both the EU and national institutions. During the past two-three years, the situation has improved, however.

The trust toward the Union and the national institutions is inversely related to economic development: the weak economic development has undermined the credibility of both the EU and national institutions.

One conclusion is that the mistrust towards the EU is not clearly distinguishable as its own phenomenon. It is a question of a common legitimacy crisis strengthened by weak economic development, which hits both the European Union and the national politics of the member states alike. When the situation improves, the political atmosphere will be more prone to EU institutional reforms.

Problems are involved in the democratic legitimacy of the Union, however. In particular, they are linked to the EU institutional division of powers becoming befuddled and opaque. The economic crisis has caused the relations between the economy, politics and law to embark in a direction which does not support democratic decision-making.

Clearer economic coordination

One of the main goals of the Lisbon Treaty concluded in 2008 was to illuminate the institutional structure of the European Union and to strengthen its role as a political operator. In the Treaty, the role of the European Parliament was strengthened, and a common external action service was created for the Union. The European Council increased the amount of qualified majority voting, and a decision was made on the President of the Council.

The outbreak of the euro crisis in 2009–2010 upset the EU’s institutional balance in a major way. Particularly in dealing with the Greek debt crisis, the tools of the European Monetary and Economic Union to solve the crisis were proven inadequate. The situation was remedied in the spring of 2010 by bilateral loans and a new crisis management tool, European financial stability mechanism (later called European Financial Stability Facility). In 2013, it was replaced by a permanent European Stability Mechanism, ESM.

The arrangement involved many legal details. The most important were issues related to so called no bail-out programmes, reforming the EU Treaty with respect to the crisis management mechanism (Treaty on the functioning of the European Union, SEUT 136) and the reformed fiscal management system, Fiscal compact, which gave the Commission more powers to monitor the debt and deficit criteria defined in the Treaty. Germany and France initiated the economic steering and it was agreed outside the Treaties in the framework of international law. However, with respect to Greek’s loan programmes, the Eurogroup took a prominent position, and it does not have an official role in the EU Treaties.

When the crisis extended, the European Central Bank also played a vital role with its asset purchase programme of 2012, so-called OMT programme, which helped to reduce the interest rates of state loans. Mario Draghi’s decision to make all that is necessary to maintain the eurozone may be considered the most critical decision of the entire euro crisis.

This development also shows what an opaque system the European Union has become because of the crisis. The institutions with executive powers such as the EU Commission and the European Central Bank have claimed a key role as economic operators. At the same time, the rules of the stability mechanism ensure that no decisions will be made on rescue packages without the approval of the big member states. Their role shows e.g. in the supervision of Greek’s third loan programme, which has largely remained the task of the Eurogroup.

Discussion on deepening the EMU cooperation often involves the question of strengthening solidarity. This is only one dimension of the conversation, however. It is equally important to see the EMU reforms as part of the larger discussion on making the EU decision-making system more transparent. The Commission has begun to clarify economic coordination by binding the crisis management mechanisms more tightly to the EU Commission and its decision-making.

New intergovernmentalism and European Parliament elections

The importance of intergovernmental cooperation has been heightened after the euro crisis. The close collaboration between Germany and France and the increasing importance of the Eurogroup are good examples of the importance of inter-governmentalism.

The first impact is that the decisions made within the EU are increasingly dependent on the domestic policies of individual countries, for example the outcome of national elections. A major shift in power balance in the political power relations of a big country like Germany or France can quickly lead to a very unstable environment. An individual country may, if it so wishes, complicate development on several policy areas.

It is not at all clear that in the development of the EMU, focusing on inter-governmentalism would benefit the small countries. In the long run, it should be the objective of Finland to clarify the national and EU level power relations and seek to strengthen the democratic legitimacy of the EU.

The second impact is that not all the reforms rely solely on the official structures of the Union. Many member states have sought to build European cooperation through intergovernmental means, outside the EU law. For example, Germany has recently formed bilateral agreements on the return of migrants as a response to the inability of the EU to promote a common asylum policy. The French initiative on a European intervention force is an example of the same development.

In the long run, it should be the objective of Finland to clarify the national and EU level power relations and to strengthen the democratic legitimacy of the EU.

The European Parliament elections of 2019 may mark a turning point in the development. At the moment, it looks like the nationalist right is closing ranks. If the normal Commission-led EU decision-making is stalled because of the elections, it may mean an even stronger shift toward intergovernmental cooperation.

This is an article of the online publication Future of Europe.

© SOSTE Finnish Federation for Social Affairs and Health, February 2019